Reactivity in Chemistry

Reactions Under Orbital Control

OC9. Decarboxylations

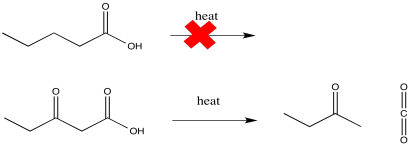

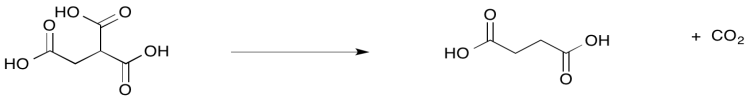

Decarboxylation refers to the loss of carbon dioxide from a molecule. This event generally happens upon heating certain carboxylic acids. It can't be just any compound; most commonly, there must be a carbonyl group β- to the carboxylic acid functional group.

Figure OC9.1. Decarboxylation is the loss of carbon dioxide from a compound.

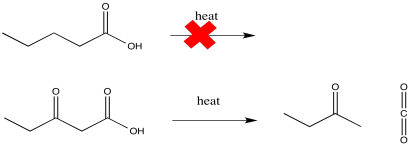

The presence of the second carbonyl in that position is crucial in stabilizing the transition state of the reaction. If we try to follow the reaction using curved arrows, we can see something similar to what we have already observed in pericyclic reactions such as the Cope rearrangement. Three pairs of electrons in a six-membered ring are responsible for the reaction.

Figure OC9.2. The mechanism of decarboxylation.

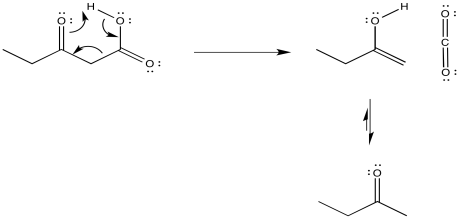

The loss of carbon dioxide from β-keto acids and esters is a key event in some important processes. Some typical synthetic methods include the acetoacetic ester synthesis and the malonic ester synthesis. These are two methods of α-alkylation. In these approaches, the presence of a carbonyl β- to a second carbonyl makes it much easier to remove the α-proton in between. That means simple bases such as sodium ethoxide are good enough to remove the proton efficiently and allow an alkylation reaction. However, once it is no longer needed for this activating effect, one of the ester groups can then be removed via decarboxylation.

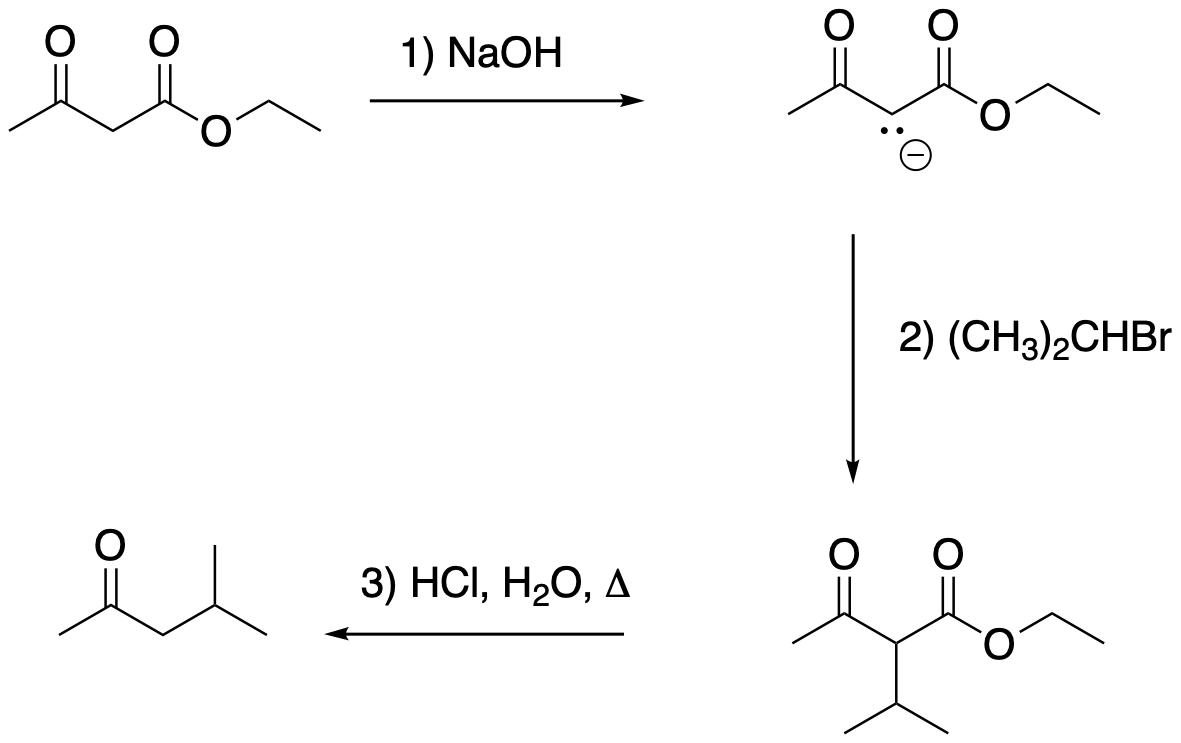

Figure OC9.3. An acetoacetic ester synthesis starts with ethyl acetoacetate and forms a ketone.

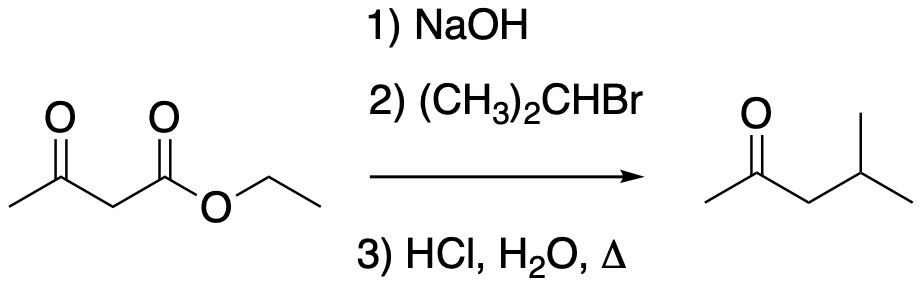

An acetoacetic ester synthesis typically starts with ethyl acetoacetate, which has a keto group β- to an ester. The doubly activated α- position is readily deprotonated to make the enolate nucleophile. At that point, any alkyl halide can be used to extend the carbon chain. Finally, decarboxylation is accomplished with heat under acidic conditions.

Figure OC9.4. A step-by step look at acetoacetic ester synthesis.

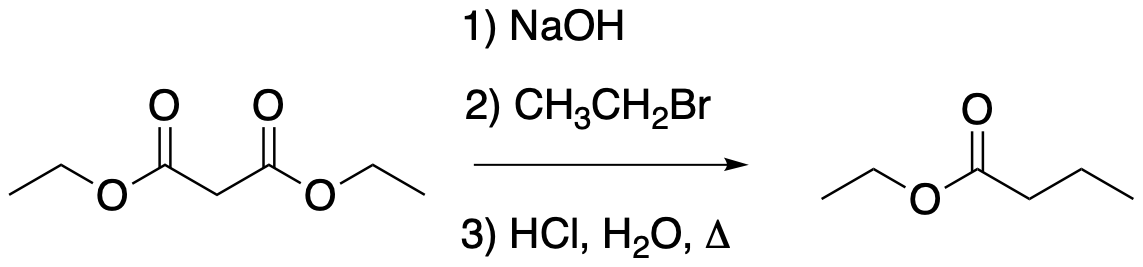

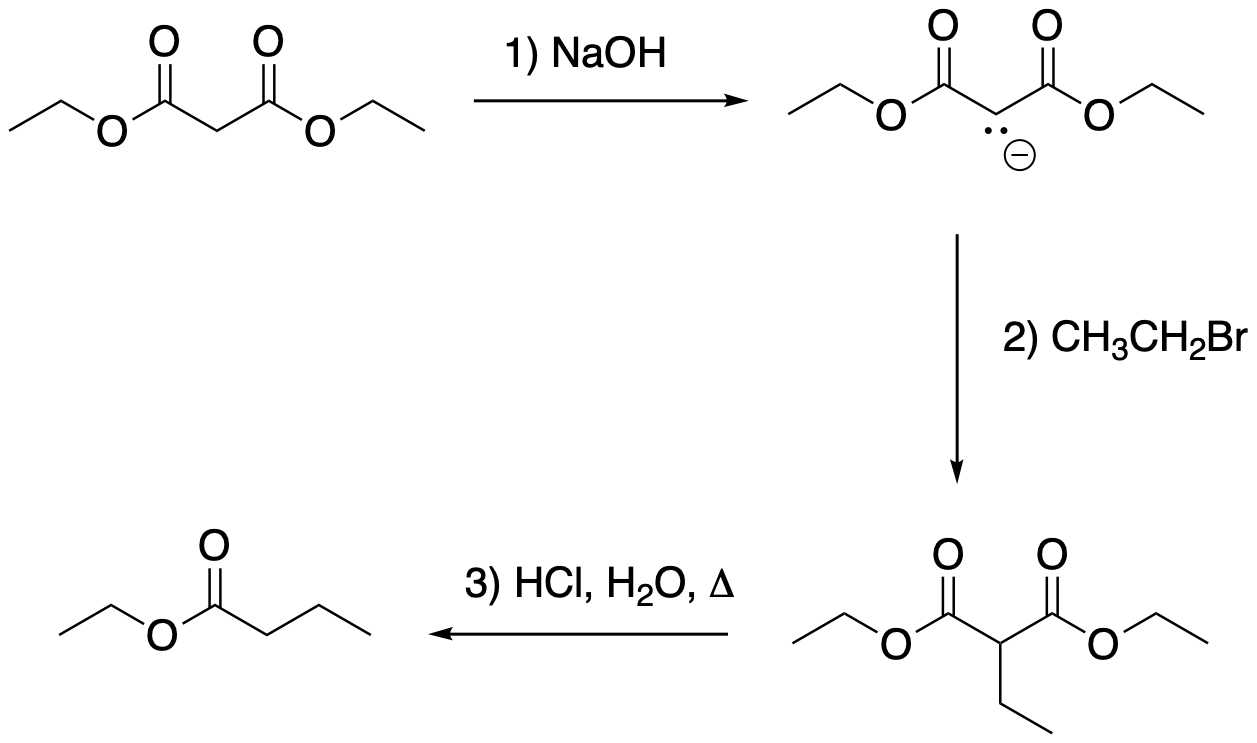

A malonic ester synthesis is very similar. It starts with a malonic ester, such as diethyl malonate, and leads to a longer-chain ester.

Figure OC9.5. A malonic ester synthesis starts with ethyl malonate and forms an ester.

The individual steps are very similar to the ones seen in the acetoacetic ester synthesis.

Figure OC9.6. A step-by step look at malonic ester synthesis.

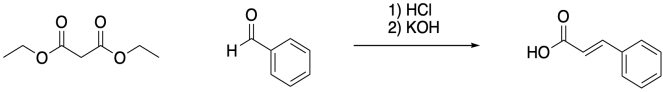

The Knoevenagel reaction is a third, related example of a synthetic transformation that relies on decarboxylation. It differs from the other two in that it involves a carbonyl condensation rather than an alylation. Once again, the reaction is followed by decarboxylation.

Figure OC9.7. The Knoevenagel reaction.

Decarboxylations are also common in biochemistry. For example, loss of CO2 from isocitrate provides α-ketoglutarate. This step is one of several exergonic events in the citric acid cycle.

Figure )C9.8. Decarboxylation of isocitrate to make succinate.

Problem OC9.1.

Provide a mechanism for the conversion of isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate.

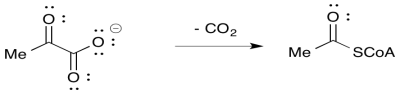

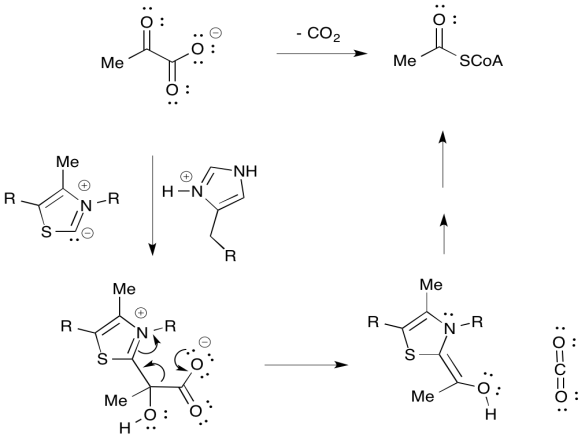

Many reactions in biochemistry involve decarboxylations, even without a stabilizing group in the β-position. For example, in the entry point to the citric acid cycle, pyruvate is decarboxylated during the formation of acetyl coenzyme A.

However, a closer look at the mechanistic pathways of these reactions reveals there is something more going on. Intermediate steps involve the introduction of these stabilizing groups, which are later removed again. In the case of pyruvate decarboxylation, the compound must be activated by the addition of a thiamine ylide. The iminium group in the resulting intermediate plays the same role as that of the β -keto group in the decarboxylations we have already seen.

Subsequent steps result in the loss of the thiamine group and its replacement with a thioester linkage.

Problem OC9.2.

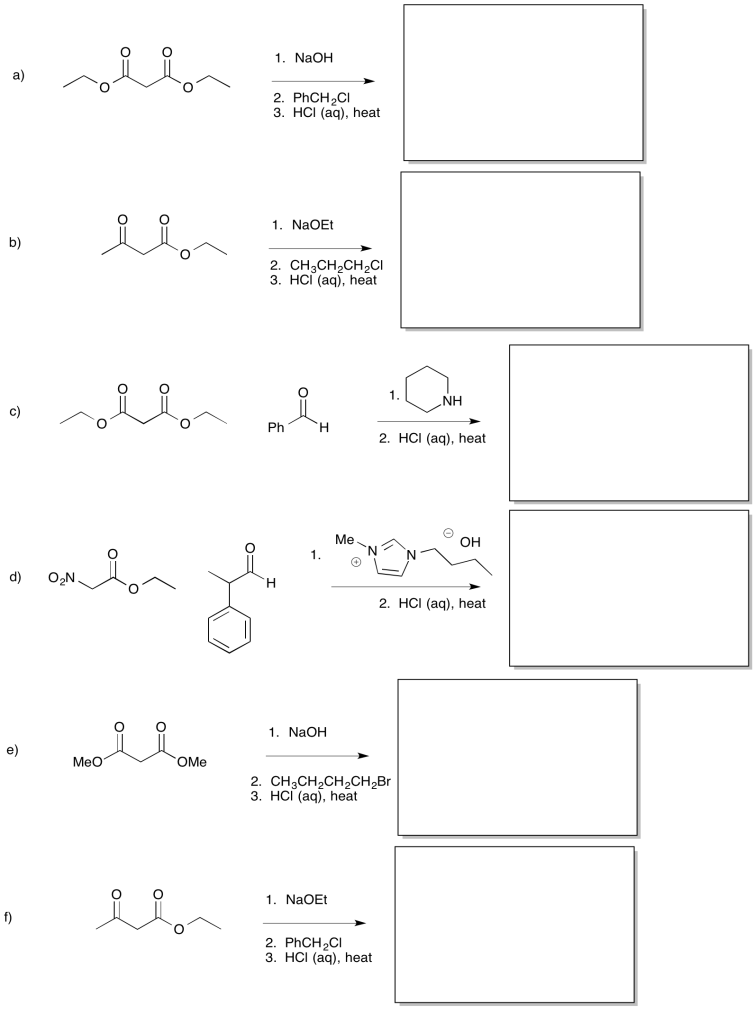

Provide products for each of the following reactions.

Problem OC9.3.

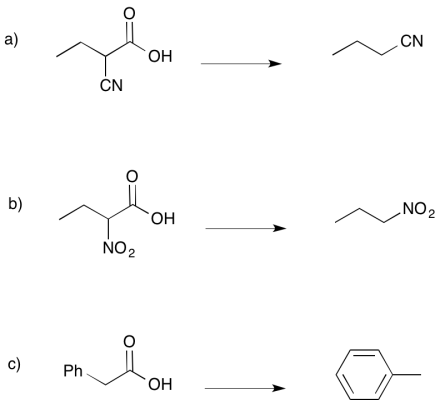

Carbonyls are not the only groups that can promote decarboxylation. Provide a mechanism for each of the following reactions.

Problem OC9.4.

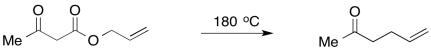

Provide a mechanism for the Carroll Reaction, which involves the initial formation of an enol intermediate.

This site was written by Chris P. Schaller, Ph.D., College of Saint Benedict / Saint John's University (retired) with contributions from other authors as noted. It is freely available for educational use.

Structure & Reactivity in Organic, Biological and Inorganic Chemistry by Chris Schaller is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1043566.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Navigation: